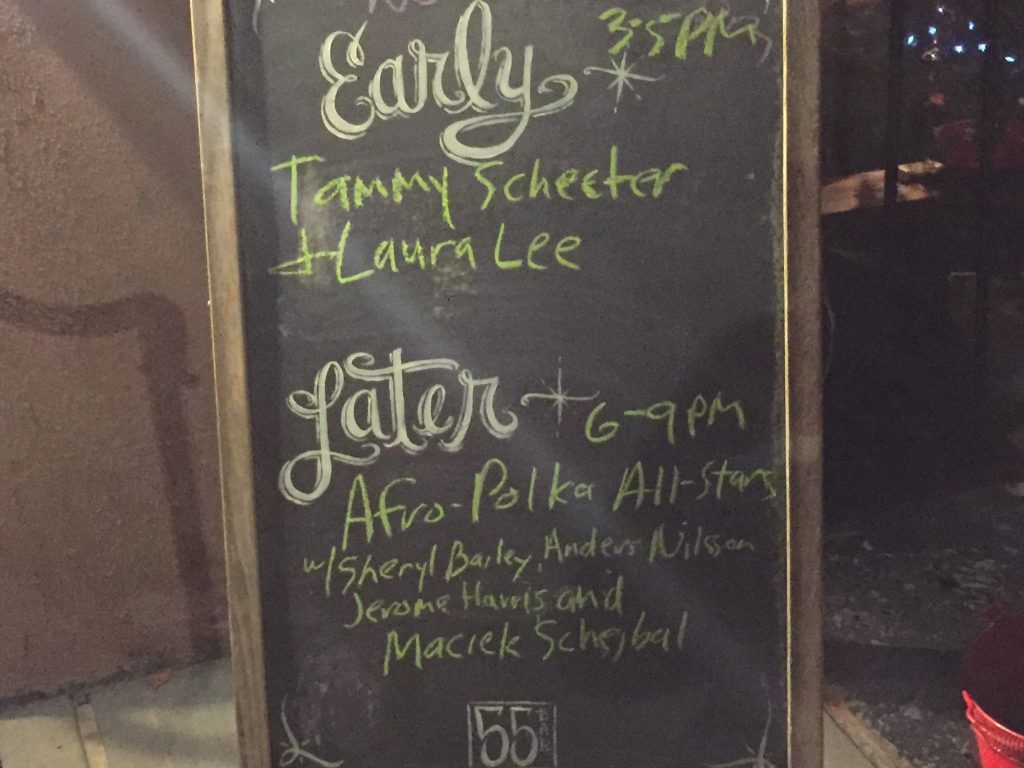

Featuring guitarists Sheryl Bailey and Anders Nilsson

Drummer/composer/world-music explorer Maciek Schejbal’s Afro-Polka project is based on the inspired, if unlikely, idea that polka, elements of African pop, and jazz guitar improvisation can be fused into a complementary whole. On the penultimate night of 2018, Schejbal, bassist Jerome Harris, and the potent guitar team of Sheryl Bailey and Anders Nilsson realized Schejbal’s thesis. Throughout three sets in front of a Sunday night, early-show, standing-room-only crowd, the Afro-Polka All-Stars explored the landscape of a new musical moon—one that offers frequent surprises, while also maintaining contact with the ears of ordinary Earthlings.

I know very little about African music—a big tent!—and less about traditional Polish music, but from what I could tell, both are integral to Schejbal’s drumming and compositions. It seems right to say that the drummer/composer’s intuition of the Polish-African rhythmic complementarity defines the sound he’s after. His drumming uses complex and catchy patterns that avoid the stylistic markers, clichés, and flourishes of rock, jazz, and fusion drumming. The patterns—both the elements coming from African angles and Polish angles, alike—are mostly straight in feel, without much swing. Schejbal’s melodies are also bi-culturally (at least) informed. A band member suggested to me that Schejbal drew melodic inspiration from traditional Polish drinking songs. And, during the set, he referenced South Africa, where he lived and absorbed music before moving to New York in the early 90s. A listener who is casually acquainted with some of the nodes at which African music has filtered into Western popular music, such as Paul Simon’s Graceland, will hear some familiar sounds, though the depth of Schejbal’s experience with African music serves notice that his music isn’t merely echoing superficial features.

Some tunes featured head sections during which Bailey and Nilsson played in major-key-based counterpoint, emphasizing intervals of thirds and sixths and occasionally interlocking in bubbling funk-like patterns. My general impression was that the heads of Schejbal’s tunes were designed to deemphasize the relationship between the main melodic instrument and its harmonic comping support found in much jazz. While the interplay between Bailey and Nilsson on heads didn’t always seem like a dialogue between equal voices, it was interactive in a way that poked through spotlight-versus-support hierarchy.

As soloists, Bailey and Nilsson both made use of major-pentatonic ideas, which fit in nicely with African-style chording, but both also veered into jazz-fusion territory. To my ear, Bailey’s solos offered the ensemble’s strongest dose of bebop influence—a reference point that never seems far away in her playing, and for which she is well-known. Through long lines made up of tremolo-picked thirds, her solos also kept a leg in the music’s contemporary African sound. Nilsson’s soloing included angular middle-Eastern inflected licks that sounded bluesy but not particularly American. Early in the evening, both players stayed relatively inside and their peaks seemed a little restrained, but as the band dug deeper into the second and third sets, the overdrives were activated and the guitar tones and soloing got more aggressive. Bailey’s drive–generated via a custom McCurdy T-style (or so I believe), an array of pedals, and a Fender-style amp—was the smoother of the two. Nilsson favored more bite from his Gibson Les Paul through a cocked-wah boost into an old Gibson amp. It may have been that Bailey’s guitar sounded a bit less forward because it literally was a bit less forward. Her amp was positioned several feet behind Nilsson’s, closer to the bass amp and with the drums between it and Nilsson’s amp.

On several tunes, Schejbal’s augmented the band’s sound by triggering samples of voices and horns in order to maintain verisimilitude between the recorded versions and the live performance. I had not encountered the use of recorded tracks before at the 55 Bar, so I found them slightly jarring. But, this was not a typical jazz gig, and they did not detract from the overall spontaneity of the performances, perhaps because the band never came off as constrained by their use. Now that I have had the opportunity to listen to the studio versions, it seems to me that there were some moments of improvisation in relation to the recordings. On one recording-enhanced tune, Bailey climaxed a solo with a dense, tightly-picked fusillade that ended in perfect synchronization with the sample. She gave a visible gesture of relief to her bandmates, as if she had just stuck a landing at the end of complex gymnastic floor program. Perhaps the inflexibility of recorded parts made for a greater-than-usual chance that an ending a little off the mark would have been glaringly obvious.

Schejbal’s Afro-Polka album was released in mid-June of 2018. Other than Schejbal, it’s not immediately clear to me who played on the album. Based on both the gig I witnessed and videos available on YouTube, the Afro-Polka lineup shifts. Schejbal has gigged with an Afro-Polka Trio, as well as the Afro-Polka All-Stars configuration, which has consistently been a quartet. In one video, Bailey is paired on guitar with Jerome Harris, who played bass on this late 2018 gig. A recent trio recording includes Nilsson on guitar and Harris on bass. At any rate, Schejbal’s Afro-Polka project is young, and, as of this late March 2019 writing, has probably not gigged more than half-a-dozen times. It is certainly worth checking out future gigs from this original, fun, adventurous, and still-developing group. Be sure to also check out the links below.

Check out some Afro-Polka links . . .

http://www.afropolka.com/index.html

Much information about Schejbal’s career, interests, books, studio, and projects. Also contains links to a variety of sources from which the Afro-Polka album can be purchased.